As fascinating as books themselves are the connections between books, the curious ways in which books inform and echo each other, creating strange synergies completely outside their authors' purview. In celebration of these connections, we've paired recent Canadian books of note, creating ideal literary companions. Because the only thing better than a book you can't wait to read is TWO of them.

*****

To Speak for the Trees, by Diana Beresford-Kroeger and Treed, by Ariel Gordon

Poetry and botany meet in these two books that celebrate the wonder and awesomeness of trees.

About To Speak for the Trees: When Diana Beresford-Kroeger—whose father was a member of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy and whose mother was an O'Donoghue, one of the stronghold families who carried on the ancient Celtic traditions—was orphaned as a child, she could have been sent to the Magdalene Laundries. Instead, the O'Donoghue elders, most of them scholars and freehold farmers in the Lisheens valley in County Cork, took her under their wing. Diana became the last ward under the Brehon Law. Over the course of three summers, she was taught the ways of the Celtic triad of mind, body and soul. This included the philosophy of healing, the laws of the trees, Brehon wisdom and the Ogham alphabet, all of it rooted in a vision of nature that saw trees and forests as fundamental to human survival and spirituality. Already a precociously gifted scholar, Diana found that her grounding in the ancient ways led her to fresh scientific concepts. Out of that huge and holistic vision have come the observations that put her at the forefront of her field: the discovery of mother trees at the heart of a forest; the fact that trees are a living library, have a chemical language and communicate in a quantum world; the major idea that trees heal living creatures through the aerosols they release and that they carry a great wealth of natural antibiotics and other healing substances; and, perhaps most significantly, that planting trees can actively regulate the atmosphere and the oceans, and even stabilize our climate.

This book is not only the story of a remarkable scientist and her ideas, it harvests all of her powerful knowledge about why trees matter, and why trees are a viable, achievable solution to climate change. Diana eloquently shows us that if we can understand the intricate ways in which the health and welfare of every living creature is connected to the global forest, and strengthen those connections, we will still have time to mend the self-destructive ways that are leading to drastic fires, droughts and floods.

About Treed: With intimacy and humour award-winning poet Ariel Gordon walks us through the streets of Winnipeg and into the urban forest that is, to her, the city's heart. Along the way she shares with us the lives of these urban trees, from the grackles and cankerworms of the spring, to the flush of mushrooms on stumps in the summer and through to the red-stemmed dogwood of the winter. After grounding us in native elms and ashes, Gordon travels to BC's northern Rockies, to Banff National Park and a cattle farm in rural Manitoba, and helps us to consider what we expect of nature. Whether it is the effects of climate change on the urban forest or foraging in the city, Dutch elm disease in the trees or squirrels in the living room, Gordon delves into our relationships with the natural world with heart and style. In the end, the essays circle back to the forest, where the weather is always better and where the reader can see how to remake even the trees that are lost.

*

What the Oceans Remember, by Sonja Boon and Tiny Lights for Travellers, by Naomi K. Lewis

Two books that travel far across both time and geography to make sense of identity and the present.

About What the Oceans Remember: Author Sonja Boon’s heritage is complicated. Although she has lived in Canada for more than thirty years, she was born in the UK to a Surinamese mother and a Dutch father. Boon’s family history spans five continents: Europe, Africa, Southeast Asia, South America, and North America. Despite her complex and multi-layered background, she has often omitted her full heritage, replying “I’m Dutch-Canadian” to anyone who asks about her identity. An invitation to join a family tree project inspired a journey to the heart of the histories that have shaped her identity. It was an opportunity to answer the two questions that have dogged her over the years: Where does she belong? And who does she belong to?

Boon’s archival research—in Suriname, the Netherlands, the UK, and Canada—brings her opportunities to reflect on the possibilities and limitations of the archives themselves, the tangliness of oceanic migration, histories, the meaning of legacy, music, love, freedom, memory, ruin, and imagination. Ultimately, she reflected on the relevance of our past to understanding our present.

Deeply informed by archival research and current scholarship, but written as a reflective and intimate memoir, What the Oceans Remember addresses current issues in migration, identity, belonging, and history through an interrogation of race, ethnicity, gender, archives and memory. More importantly, it addresses the relevance of our past to understanding our present. It shows the multiplicity of identities and origins that can shape the way we understand our histories and our own selves.

About Tiny Lights for Travellers: Why couldn’t I occupy the world as those model-looking women did, with their flowing hair, pulling their tiny bright suitcases as if to say, I just arrived from elsewhere, and I already belong here, and this sidewalk belongs to me?

When her marriage suddenly ends, and a diary documenting her beloved Opa’s escape from Nazi-occupied Netherlands in the summer of 1942 is discovered, Naomi Lewis decides to retrace his journey to freedom. Travelling alone from Amsterdam to Lyon, she discovers family secrets and her own narrative as a second-generation Jewish Canadian. With vulnerability, humour, and wisdom, Lewis’s memoir asks tough questions about her identity as a secular Jew, the accuracy of family stories, and the impact of the Holocaust on subsequent generations.

*

You Won't Always Be This Sad, by Sheree Fitch and Notes from the Everlost, by Kate Inglis

Grief and love intertwine in these heartrending and generous memoirs of bereavement.

About You Won't Always Be This Sad (coming October 2019):

"You won't always be this sad," her mother, who also lost a son, reassures her, while a close friend encourages her to pick up the pen and write it all down. Capturing her own struggles as she emerges from shock in the wake of her son's unexpected death at age 37, author and storyteller Sheree Fitch writes lyrically and unabashedly, with deep sorrow, unexpected rage, and boundless love. She discovers that she "dwells in a thin place now," that she has crossed a threshold only to find herself in "the quicksand that is grief." The result is a memoir in verse of immense power and pain, a collection of moments, and a journey of resilience.

Divided into three parts, like the memorial labyrinth Fitch walks every day, You Won't Always Be This Sad offers words that will stir the heart, inviting readers on a raw and personal odyssey through excruciating loss, astonishing gratitude, and a return to a different world with new insights, rituals, faith, and hope. Readers, bearing witness to the immeasurable depths of a mother's love, will be forever changed.

About Notes from the Everlost:

Part memoir, part handbook for the heartbroken, this powerful, unsparing account of losing a premature baby will speak to all who have been bereaved and are grieving, and offers inspiration on moving forward, gently integrating the loss into life.

Inglis’s story is a springboard that can help other bereaved parents—and anyone who has experienced wrenching loss—reflect on emotional survival in the first year; dealing with family, friends, and bystanders post-loss; the unique survivors’ guilt, feelings of failure, and isolation of bereavement; and the fortitude of like-minded community and small kindnesses. Inglis’s unique voice—at once brash, irreverent, and achingly beautiful—creates a nuanced picture of the landscape of grief, encompassing the trauma, the waves of disbelief and emptiness, the moments of unexpected affinity and lightness, and the compassion that grows from our most intense chapters of the human experience.

*

A World Without Martha, by Victoria Freeman and Shut Away, by Catherine McKercher

Two writers reflect on changing attitudes about regarding disability and their own family stories in these memoirs about siblings who spent their lives in institutions.

About A World Without Martha: Victoria Freeman was only four when her parents followed medical advice and sent her sister away to a distant, overcrowded institution. Martha was not yet two, but in 1960s Ontario there was little community acceptance or support for raising children with intellectual disabilities at home. In this frank and moving memoir, Victoria describes growing up in a world that excluded and dehumanized her sister, and how society’s insistence that only a “normal” life was worth living affected her sister, her family, and herself, until changing attitudes to disability and difference offered both sisters new possibilities for healing and self-discovery.

About Shut Away: "How many brothers and sisters do you have?" It was one of the first questions kids asked each other when Catherine McKercher was a child. She never knew how to answer it.

Three of the McKercher children lived at home. The fourth, her youngest brother, Bill, did not. Bill was born with Down syndrome. When he was two and a half, his parents took him to the Ontario Hospital School in Smiths Falls and left him there. Like thousands of other families, they exiled a child with disabilities from home, family, and community.

The rupture in her family always troubled McKercher. Following Bill's death in 1995, and after the sprawling institution where he lived had closed, she applied for a copy of Bill's resident file. What she found shocked her.

Drawing on primary documents and extensive interviews, McKercher reconstructs Bill's story and explores the clinical and public debates about institutionalization: the pressure to "shut away" children with disabilities, the institutions that overlooked and sometimes condoned neglect and abuse, and the people who exposed these failures and championed a different approach.

*

Dance Me To the End (coming in October), by Alison Acheson and A Victory Garden for Trying Times, by Debi Goodwin

Two books about surviving the loss of a spouse to illness.

About Dance Me To the End: A profoundly honest and intensely personal story of a woman who cares for her husband after the devastating terminal diagnosis of ALS.

Marty, age 57, was given a preliminary diagnosis of ALS by his family doctor. Seven weeks later, the diagnosis was confirmed by a neurologist. Ten months and ten days later, Marty passed away.

From day one, Alison, Marty’s spouse of over twenty-five years, kept a journal as a way to navigate the overwhelming state of her mind and soul. Soon the rawness of her words harmonized to tell the story of Marty’s diagnosis, illness, and decline. Her journal became a chronicle of caregiving as well as an emotional exploration of the tensions between the intuitive and the pragmatic, the logical and illogical, and the all-consuming demands of being both spouse and nurse. Divided into short pieces, some of which reads as free verse, Alison’s words are at times profoundly intense and painfully private.

The composition of the intricate notes of a life in its final movements includes another stanza of the journal that became Dance Me to the End: the guiding of children grappling with the imminent loss of a parent, and the shifting roles of family, friends, and community—all of which add their own complex rhythms.

About A Victory Garden for Trying Times: Ever since her childhood on a Niagara farm, Debi has dug in the dirt to find resilience. But when her husband, Peter, was diagnosed with cancer in November, it was too late in the season to seek solace in her garden. With idle hands and a fearful mind, she sought something to sustain her through the months ahead. She soon came across Victory Gardens—the vegetable gardens cultivated during the world wars that sustained so many.

During an anxious winter, she researched, drew plans, and ordered seeds. In spring, with Peter in remission, her garden thrived and life got back on track. But when Peter's cancer returned like a killing frost, the garden was a reminder that everything must come to an end.

A Victory Garden for Trying Times is a personal journey of love, loss, and healing through the natural cycles of the earth.

*

The Mosquito, by Timothy C. Winegard and In the Valleys of the Nobel Beyond, by John Zaida

One creature tiny and ubiquitous, the other huge and elusive—these two make for illuminating reads about the mysteries and wonders of the natural world.

About The Mosquito: Why was gin and tonic the cocktail of choice for British colonists in India and Africa? What does Starbucks have to thank for its global domination? What has protected the lives of popes for millennia? Why did Scotland surrender its sovereignty to England? What was George Washington's secret weapon during the American Revolution?

The answer to all these questions, and many more, is the mosquito.

The mosquito has determined the fates of empires and nations, razed and crippled economies, and decided the outcome of pivotal wars, killing nearly half of humanity along the way. She (only females bite) has dispatched an estimated 52 billion people from a total of 108 billion throughout our relatively brief existence. As the greatest purveyor of extermination we have ever known, she has played a greater role in shaping our human story than any other living thing with which we share our global village.

Driven by surprising insights and fast-paced storytelling, The Mosquito is the extraordinary untold story of the mosquito’s reign through human history and her indelible impact on our modern world order.

About In the Valleys of the Noble Beyond: Canada’s Great Bear Rainforest is home to trees as tall as skyscrapers and moss as thick as carpet. According to the people who live there, another giant may dwell in these woods. For centuries, locals have reported encounters with the Sasquatch—a species of hairy man-ape that could inhabit this pristine wilderness. Driven by his childhood obsession with the Sasquatch, yet trying to remain objective, journalist John Zada seeks out the people and stories surrounding this enigmatic creature. He speaks with local Indigenous peoples and a Sasquatch-studying scientist. He hikes with a former bear hunter. Soon, he finds himself on quest for something infinitely more complex, cutting across questions of human perception, scientific inquiry, Indigenous traditions, the environment, and the power of the human imagination to believe in—or to outright dismiss—one of nature’s last great mysteries.

*

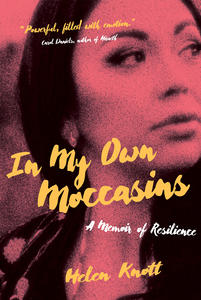

In My Own Moccasins, by Helen Knott and Falling for Myself, by Dorothy Ellen Palmer

Two highly anticipated memoirs about resilience and reckoning with past and future.

About In My Own Moccasins: Helen Knott, a highly accomplished Indigenous woman, seems to have it all. But in her memoir, she offers a different perspective. In My Own Moccasins is an unflinching account of addiction, intergenerational trauma, and the wounds brought on by sexual violence. It is also the story of sisterhood, the power of ceremony, the love of family, and the possibility of redemption.

With gripping moments of withdrawal, times of spiritual awareness, and historical insights going back to the signing of Treaty 8 by her great-great grandfather, Chief Bigfoot, her journey exposes the legacy of colonialism, while reclaiming her spirit.

About Falling for Myself: In this searing and seriously funny memoir, Dorothy Ellen Palmer falls down, a lot, and spends a lifetime learning to appreciate it. Born with congenital anomalies in both feet, then called birth defects, she was adopted as a toddler by a wounded 1950s family who had no idea how to handle the tangled complexities of adoption and disability. From repeated childhood surgeries to an activist awakening at university to decades as a feminist teacher, mom, improv coach and unionist, she tried to hide being different.

But now, in this book, she's standing proud with her walker and sharing her journey. With savvy comic timing that spares no one, not even herself, Palmer takes on Tiny Tim, shoe shopping, adult diapers, childhood sexual abuse, finding her birth parents, ableism and ageism. In Falling for Myself, she reckons with her past and with everyone's future, and allows herself to fall and get up and fall again, knees bloody, but determined to seek Disability Justice, to insist we all be seen, heard, included and valued for who we are.

Comments here

comments powered by Disqus