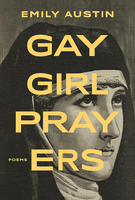

Hauntings form the canopy of The Seventh Town of Ghosts (March), the debut by Faith Arkorful, CBC Poetry Prize finalist and National Magazine Award honoree. The extreme level of sass in Emily Austin's Gay Girl Prayers (March) does not mean that this collection is irreverent, on the contrary, in rewriting Bible verses to affirm and uplift queer, feminist, and trans realities, Austin invites readers into a giddy celebration of difference and a tender appreciation for the lives and perspectives of "strange women." Uiesh / Somewhere (May), consists of short poems arising from Joséphine Bacon’s experience as an Innu woman, whose life has taken her from the nomadic ways of her Ancestors in the northern wilderness of Nitassinan, or Innu Territory, to the clamour and bustle of the city.

And in I Will Get Up Off Of (May), by Simina Banu, poems are attempts and failures at movement as the speaker navigates her anxiety and depression in whatever way she can, looking for hope from social workers on Zoom, wellness influencers, and psychics alike.

Award-winning writer Joelle Barron looks back at history through queer eyes in their second poetry collection, Excerpts from a Burned Letter (April). Anatomical Venus (April), by Courtney Bates-Hardy, is a visceral collection of poems that invoke anatomical models, feminine monsters, and little-known historical figures, and a journey through car accidents and physio appointments, 18th century morgues and modern funeral homes. And in The Weight of Survival (February), Tina Biello retraces her family’s journey from post-war Italy to a small logging town near Cowichan Lake, exploring themes of identity, queerness and belonging.

Tim Bowling’s latest collection, In the Capital City of Autumn (April), threads autumnal themes such as the loss of his mother and the demolition of his childhood home, his children growing and the inevitable passage of time. In twofold (April), Edward Carson gathers concise diptych—or twofold—poems exploring themes of love, relationships, myth, art, language, math, physics, geometry, and artificial intelligence. Borrowing and disrupting the forms of patient records, psychiatric assessments, and court documents, Jody Chan's impact statement (March) traces a history of psychiatric institutions within a settler colonial state.

In this arresting debut collection Blood Belies (April), Ellen Chang-Richardson writes of race, of injury and of belonging in stunning poems that fade in and out of the page. That Audible Slippage (February), by Margaret Christakos, invokes a poetics of active listening and environmental sound to investigate the ways in which we interact with the world, balancing perception and embodiment alongside a hypnagogic terrain of grief and mortality. And hermetic and beguiling, sensuous and musical, Sorry About the Fire (April), by Coco Collins, introduces not just a poet, but a stunningly original sensibility.

How do we redefine the self when memory begins to deteriorate? This question is at the heart of Rob Colman’s Ghost Work (February), a suite of poems that explores a son's gradual loss of his father from dementia. Honest, elegiac, characteristically strange, and frequently funny, Kayla Czaga’s Midway (April) is an exploration of grief in all its manifestations. The poems in Dina Del Bucchia's You’re Gonna Love This (April) track the narrator’s entwined relationships with her spouse, her television, and herself. And The Chrome Chair (April) is Newfoundland feminist environmentalist poetry at its finest, Danielle Devereaux’s sharp, humorous writing cutting to the heart of contemporary concerns around feminism and climate change through playful re-imaginings of the life of Rachel Carson, and wry critiques of Newfoundland politics.

Triangulated against the backdrop of a deteriorating world, Em Dial’s In the Key of Decay (May) pushes past borders both real and imagined to attend to those failed by history. A sometimes satirical reflection on hope in a time of hopelessness, the poems in Ali Duff’s I Dreamed I Was an Afterthought (May) use stubborn humour to grapple with the anxiety of moving forward during late capitalism. To describe the writing of Marilyn Dumont is to call her a poet of reclamation and resurgence, as demonstrated in Reclamation and Resurgence: The Poetry of Marilyn Dumont (April), edited by Armand Garnet Ruffo. And in Wet (May), by Leanne Dunic, a transient Chinese American model working in Singapore thirsts for the unattainable: fair labour rights, the extinguishing of nearby forest fires, breathable air, healthy habitats for animals, human connection.

A Road Map for Finding Wild Horses (May), by Trisia Eddy Woods, is written as a response to the intersections of human, animal, and land that occur while exploring the landscape as a woman alone. Patrick Grace’s Deviant (February) traces a trajectory of queer self-discovery from childhood to adulthood, examining love, fear, grief, and the violence that men are capable of in intimate same-sex relationships. And from the award-winning, multi-genre author and musician Steven Heighton, Songbook (April) brings together Heighton’s lyrics and music for the first time in a single volume, including his final songs, which have never been heard or seen until now.

Teeth (April), by Dallas Hunt (whose Creeland was nominated for the George Ryga Award for Social Awareness in Literature, Gerald Lampert Memorial Award and the Indigenous Voices Award), is a book about grief, death and longing, about the gristle that lodges itself deep into one’s gums, between incisors and canines. Donna Kane’s Asterisms (March) is an eclectic collection that celebrates the universe and the natural world of which we are all a part. Nominated for a Governor General's Literary Award, The Pear Tree Pomes (May), by Roy Kiyooka, illustrated by David Bolduc, won fans in well-known writers and artists across Canada, and this reissue includes new archival material, giving readers the opportunity to (re)discover this graceful collaboration of poetry and art and the story behind it.

Chief Stacey Laforme breathes life into every poem and story he shares, drawing from his own experiences in Love Life Loss and a little bit of hope (March). Situated at the moment when thought becomes image, lettuce lettuce please go bad (April) expands on Tiziana La Melia’s personal history of familial migration and agricultural labour—picking, pruning, grafting, tending, planting—entangled in issues of colonization, land manipulation, ownership, extraction, and food production. The poems in Empires of the Everyday (March), by Anna Lee-Popham, give voice to the many “you” who move through a city—one that resembles many modern cities—where plywood shelters are demolished in pandemic winters, where everyday violence is palpable, but the related media reporting is offhand, cool, distanced, piecemeal, uncontextualized. Splicing Byronic rhymes and Auden’s meters with twenty-first century irreverence and the profane juxtaposition of a late-stage Twitter feed, the poems in Barfly (April), Michael Lista’s third collection, are alternately aggressive, humane, LOL funny, and raw with break-your-heart vulnerability.

With admiration for the land holders (trees) and inhabitants of the rainforest, wetlands and oceans of her home, former Tofino Poet Laureate Christine Lowther delves into the pressing issues of urbanization, climate change, and loss of biodiversity while expressing her deep concern for those feathered, furred, webbed, and rooted in Hazard, Home (February). In Blood of Stone (March), Tariq Malik revisits Kotli, the 1,000-year-old city of his formative years in the province of Punjab, Pakistan. For Dawn Macdonald, the North is not an escape, a pathway to enlightenment, or a lifestyle choice, but a messy, beautiful, and painful point of origin explored in Northerny (February).

David Martin’s Limited Verse (April) is an uncanny collection of familiar poems made newly strange, wrapped in a fascinating speculative mystery. Good Want (May), by Domenica Martinello, entertains the notion that perhaps virtue is a myth that’s outgrown its uses. And Crying Dress (April), acclaimed poet Cassidy McFadzean’s third book, explores the intersections between noise and coherence, the conversational and the associative, the architectural and the ecological.

Familiar Monsters of the Flood (April) is a tight, emotional, and stunning debut, Tia McLennan’s mastery of metaphor and concise word choice packs a punch in these poems about intergenerational connection, motherhood, grief, ecology and memory. Exploring the landscape of grief in the wake of divorce, Most of All the Wanting (May), by Amanda Merpaw, is a treatise on intimacy in the face of change. A drive to drug rehab, at least two murders, one escaped prisoner, a complex father/son relationship, and several highly unusual classroom experiences form the backbone of Flak Jacket (April), Gerald Arthur Moore's latest collection of his signature explosive poetry.

In Oh Witness Dey! (March), Shani Mootoo expands the question of origins, from ancestry percentages and journey narratives, through memory, story, and lyric fragments. From poet Chantal Neveu comes you (March), translated by Erín Moure, a book-length poem that plunges us more deeply into the notion of the idyll and into the polyhedric structure of love. And Melanie Marttila captures the solace and healing she has found in the terrestrial landscapes, flora, and fauna of northeastern and southwestern Ontario while balancing the ebbs and flows of her mental health in The Art of Floating (April).

Multifaceted and multi-voiced, Emily McGiffin’s poems in Into the Continent (March) explore the ongoing violence, destruction, and loss wrought by colonialism and capitalist extraction across time and geographic space, from Turtle Island to South Africa. In What Fills Your House Like Smoke (May), E. McGregor combines the lore of family history with personal memory, vividly parsing patterns of inheritance, particularly through the maternal line. And at the heart of The Knot of My Tongue (March) is Zehra Naqvi’s storying of language itself and the self-re-visioning that follows devastating personal rupture.

Jennifer May Newhook’s Last Hours (April) is a fast-paced collection of poems about motherhood, Newfoundland, poverty, mortality and the absolute mirth of being alive. With A Year of Last Things (March), Michael Ondaatje returns to poetry, where he began his career over fifty years ago. And from award-winning poet Catherine Owen, Moving to Delilah (April) is a collection of poems about one woman's journey from BC to a new life in Alberta, where she buys an old house and creates a new meaning of home.

A Fate Worse than Death (April), by Nisha Patel, is a stunning poetic investigation of the worthiness of disabled life as told through the author’s evaluation of her own medical records over the course of a decade. Expansive in form and voice, the poems in Julie Paul’s second collection Whiny Baby (April) offer both love letters and laments, taking us to construction sites, meadows, waiting rooms, beaches, alleys, gardens, and frozen rivers, from Montreal to Hornby Island. Reflexive and lyrical, the collection dayo (April), by Marc Perez, embodies the true curiosity and tenacious spirit of a dayo (a Tagalog word referring to someone who exists in a place not their own) seeking a place to replant, tend, and grow delicate roots.

Marc Plourde’s new collection, Summer in Furnished Rooms (April), tunnels into 55 years of life, retrieving episodes that may seem like fiction when viewed from the distance of time. Written in a speculative mood, the poems in Matt Rader’s Fine (April) look back on the contemporary moment with its terrors and mythopoetic digital scrim from an imagined future, so that the voice itself becomes an incantation, a summoning of a world of survivance and beauty. And grounded in the local and immediate—from Toronto’s rivers and ravines to its highways and skyscrapers—John Reibetanz’s Metromorphoses (April) explores some of the radical changes that have taken place in the city during the course of its history.

Plural, civic, and political, the poems in Jay Ritchie’s Listening in Many Publics (May) locate themselves in the many publics that constitute our individual and social being, interrogate that which brings the subject into existence, and ultimately convey an open, hopeful sensibility in the face of the structures and systems they critique. Jamie Sharpe’s fifth collection is Get Well Soon (April). Helen of Troy, Anne Boleyn, Shakuntala Devi, Hypatia of Alexandria, Marie Curie; Johanna Skibsrid’s Medium (March) interprets the voices of women vilified by history, silenced by famous husbands, forced into sex work, or wrongly accused.

The quicksilver poems in Sue Sorensens’s Acutely Life (February) are life studies, or conversations held with all sorts of unsuitable and suitable companions, written in a style full of echoes and dark humour. Cities Within Us (April), by Peter Taylor, offers poems that are dense and deep with language that resonates at multiple levels and often startles with its juxtapositions and verbal explosions. And A Blueprint for Survival (March), by Kim Trainor, begins in wildfire season, charting a long-distance relationship against the increasing urgency of climate change in the boreal, then shifts to a long sequence, “Seeds,” which thinks about forms of resistance, survival, and emergence in the context of the sixth mass extinction.

With the determination and curiosity of a problem-solving crow, Barbara Tran’s debut Precedented Parroting (February) plumbs personal archives and traverses the natural world, endeavouring to shake the tight cage of stereotypes, Asian and avian. In Realia (April), Michael Trussler grapples with the black fire of mental illness, revels in the joy inherent to colours, and probes what it means to be alive at the beginning of the Anthropocene. And modelled after the American folk music revival songbooks of the 1950s and 60s, Michael Turner’s Playlist: a Profligacy of Your Least-Expected Poems (June) documents the life and practice of a writer who grew up in a musical household, spent his early adult years as a touring musician and his later years programming nightclubs, hotels, galleries and festivals.

In Talking to Strangers (April), with gorgeous arias of recollection and evocation, of elegy and heartbreak, Rhea Tregebov mourns, praises, prays, regrets, summons, celebrates, and bears witness with formidable artistry and tenderness. Through multiple locales, languages and spiritualities, A Bouquet Brought Back from Space (April), by Kevin Spenst, both subverts and sublimates traditions of religious poetry, love poetry, and song. And Matthew Tierney’s new collection Lossless (May) takes its title from lossless data compression algorithms, and positions the sonnet as lines of code that transmit through time and space those "stabs of self," the awareness of being that intensifies with loss of relationships, of faith, of childhood, of people.

Firmly grounded in the local, the poems in Chimwemwe Undi’s debut, Scientific Marvel (April), are preoccupied with Winnipeg in the way a Winnipegger is preoccupied with Winnipeg, the way a poet might be preoccupied with herself: through history and immigration; race and gender; anxieties and observation. The Wind Has Robbed the Legs off a Madwoman (April) is a rare new book of verse from one of the most recognized and distinguished names in Newfoundland poetry and drama, Agnes Walsh. And raw, confessional, and often messy, Terrarium (April) continues Matthew Walsh’s exploration of queer identity and desire against the lonely highs and lows of depression and addiction.

In The Lantern and the Night Moths (April), Chinese diaspora poet-translator Yilin Wang has selected and translated poems by five of China’s most innovative modern and contemporary poets. Uncompromising and substantial, Derek Webster’s National Animal (April) explores our "civic moment" where "birds sing oblivion / estranged from all things," and meditates, in a final image-rich sequence, on our place in a science-based cosmos. Speaking through a cultural amnesia collected between a sunken past and a sensed, ghostly-dreamed future, shima (March), by Shō Yamagushiku, anchors this interrogation of the relationship between father and son in the fragile connective tissue of memory where the poet’s homeland is an impossible destination.

In The Last To the Party (April), a deeply moving debut, Chuqiao Yang explores family, culture, diaspora, and the self’s tectonic shifts over time. Onjana Yawnghwe returns with We Follow the River (March), a deeply personal exploration of family, memory, and self that tells the story of one family’s escape from military violence in Myanmar, their exiled existence in Thailand, and their immigration to Canada with only a pile of beat up suitcases on a luggage cart. And the poems in Daniel Zomparelli's Jump Scare (April) dig deep into mental health, neurodivergence, grief, dreams, monstrosity, sexuality, pop culture, queer consumer culture, and the commodification of identity.

Comments here

comments powered by Disqus